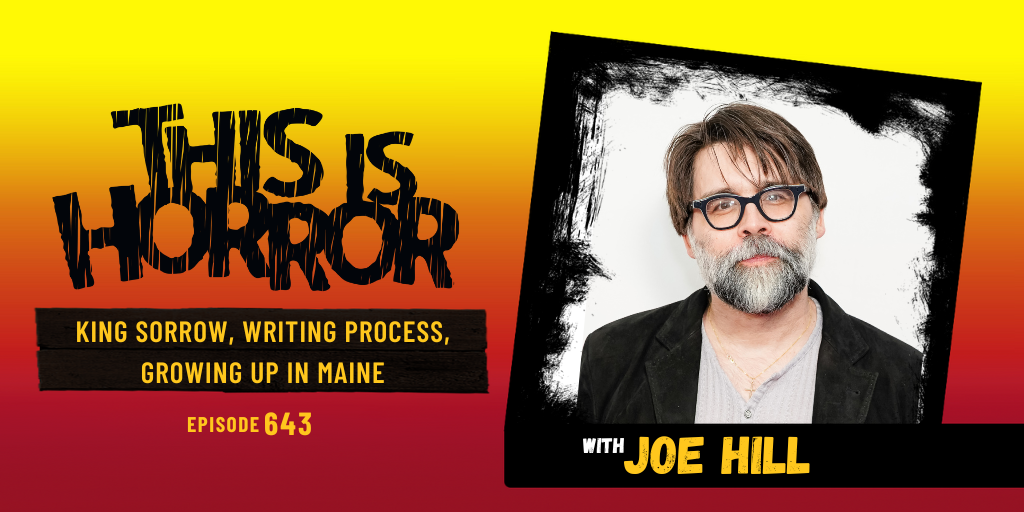

In this podcast, Joe Hill talks about King Sorrow, his writing process, growing up in Maine, and much more.

About Joe Hill

Joe Hill is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Fireman, Heart-Shaped Box, and Strange Weather. Much of his work has been adapted for film and television. His second novel, Horns, was made into a cult horror-comedy starring Daniel Radcliffe; his third novel, NOS4A2, was adapted for television by AMC, and featured Zachary Quinto; his short story The Black Phone was adapted for the big screen by Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill, and starred Ethan Hawke. In 2007, he co-created the long-running comic book Locke & Key, with artistic maestro Gabriel Rodriguez; in 2011 Hill won the Eisner Award (Best Writer) for his work on the series. The six books in the Locke & Key saga formed the basis for a hit TV series on Netflix. A seventh volume, published in 2022, married the world of Locke & Key to the epic Sandman universe. Hill’s other works include the short fiction collection Full Throttle and several graphic novels: Basketful of Heads, Plunge, Sea Dogs, Dying is Easy, and Wraith (which continues the story of NOS4A2’s Charlie Manx).

Timestamps

Thanks for Listening!

Help out the show:

- Support This Is Horror on Patreon

- Listen to This Is Horror Podcast on iTunes

- Listen to This Is Horror Podcast on Spotify

- Rate and review the This Is Horror Podcast on iTunes

- Share the episode on Facebook and Twitter

- Subscribe to This Is Horror podcast RSS Feed

Let us know how you enjoyed this episode:

- Leave us a message on SpeakPipe.

- Write a comment below.

- Tweet us @thisishorror.

Resources

- Joe Hill Books

- Watch the video version of This Is Horror Podcast episodes, including our conversation with Chuck Palahniuk on YouTube.

The Girl in the Video by Michael David Wilson, narrated by RJ Bayley

Listen to The Girl in the Video on Audible in the US here and in the UK here.

They’re Watching by Michael David Wilson and Bob Pastorella

Read They’re Watching by Michael David Wilson and Bob Pastorella right now or listen to the They’re Watching audiobook narrated by RJ Bayley.

Michael David Wilson 0:20

Welcome to This is horror, a podcast for readers, writers and creators. I'm Michael David Wilson and every episode, alongside my co host, Bob Pastorella, we chat with the world's best writers about writing, life, lessons, creativity and much more. Today we are chatting to Joe Hill, the number one New York Times best selling author of the fire man, Heart Shaped Box. Nosferatu, strange weather and his latest book, King sorrow. Now, Joe is someone whom I have wanted to speak to for a long time now. We ran an episode back with him in 2013 when my former co host Dan Howarth spoke with Joe in the back of a water stones before a UK book event promoting Nosferatu that was a 15 minute appetizer into the wonderful Mind and Life of Joe Hill. But this is the main event, as you might expect. We begin things by talking about Joe's early life. We then dive into his writing process, talk about his writing journey, and even get into why he goes by Joe Hill, rather than taking on the King family name. We also talk a little bit about his latest release, King sorrow, although sadly, the hour limit meant we didn't get to dissect it in the manner I would have liked, but we can save all of that for the next time. So I think you're gonna have a really wonderful time with this one. But before we get into it, a quick advert break

Bob Pastorella 2:35

from the host of this is horror podcast comes a dark driller of obsession, paranoia and voyeurism. After relocating to a small coastal town, Brian discovers a hole that gazes into his neighbor's bedroom every night she dances and he peeps same song, same time, same wild and mesmerizing dance. But soon, Brian suspects he's not the only one watching. She's not the only one being watched. They're watching is The Wicker Man meets body double with a splash of Suspiria. Their watching by Michael David Wilson and Bob Pastorella, is available from this is horror.co.uk,

Amazon and wherever good books are sold.

RJ Bayley 3:14

It was as if the video had unzipped my skin, slunk inside my tapered flesh and become one with me.

Bob Pastorella 3:21

From the creator of this is horror, comes a new nightmare for the digital age. The girl in the video, by Michael David Wilson, after a teacher receives a weirdly arousing video, his life descends into paranoia and obsession. More videos follow, each containing information no stranger could possibly know, but who's sending them and what do they want? The answers may destroy everything and everyone he loves. The girl in the video is the ring meets fatal attraction for the iPhone generation, available now in paperback, ebook and audio.

Michael David Wilson 3:52

Okay, without said, Here it is. It is Joe Hill on this is horror. You. Hey, Joe, welcome to this is horror. Thank you so much for having me on so to begin with, I want to go all the way back to your childhood, because I want to know what some of the early life lessons were that you learned growing up in Bangor Maine,

Joe Hill 4:22

you want me to it's you want to go all this like sitting down with my therapist. I want to take you back to your child. This is it. When I say the word mother, what's the first thought that comes to your we'll play, let's play a word association game. I'll say Mother, and you say a word. So mother, knife, Father rage, you know, no, um, no. Bangor Maine, you know, I had, I had a terrific childhood in a moderate sized town. It's not quite the small town it is. It is, you know, it's dairy in in my, my dad's books, and the, you know, the representation of it that you get in it is pretty accurate to the history of the play or the geography of the place. The history has maybe been darkened a little, but then again, maybe not that much. But the town that I grew up in, you know, it's a terrific American town, good folks, real working class town, and and I, you know, I think one of the reasons that my, you know, my parents remained extremely grounded is because they never moved out. You know, my dad just got the l just to get it out of the way. My, you know, my dad's the writer, Steve King, you know, when he when they made it when, when they hit it big. They didn't move to LA or, you know, New York City or anything. They stayed right in Bangor. My dad has been in AA for over 25 years, you know. And I think that's kept him grounded too, you know, when he talks about his peers, he's not talking about other writers, talking about drunks, you know, people he meets in the room in the, you know, in the church basement with the bad coffee, where they all introduce each other by their first names. So, you know, I think that was a really, I think it was really healthy, you know that I did. It was not a particularly sheltered childhood. It was the kind of 1980s childhood that freaks, you know, the millennials out. They see it in Stranger Things, and they think to themselves, could that really have Could you really just ride around on your bikes all day long and no one knew where you were. And I'm like, yeah, pretty much, you know, I mean, you had to be back by dark, but my parents never gave it another thought. So I think that was healthy, right? Because you got yourself into trouble. You were 10, riding around with your friends and your bikes, and you got into trouble, but you also learned you could get

Michael David Wilson 7:01

yourself out of it, right? Yeah. And I mean in terms of the stories, I will often ask people, you know, what were your first experiences with story? But you're in a unique position, because obviously your dad was writing all of these

Joe Hill 7:19

horror and my mother too. My mother is quite accomplished novelist, Tabitha King, you know, she's written, like, seven terrific American novels about, really, actually, about working class life in Maine, you know, the subject that she knows best. I mean, you know, their first years of marriage, she was, you know, the manager of a Dunkin Donuts, fighting off handsy customers. And my dad, who was a English teacher at Hampden Academy, couldn't make enough money teaching to really support the family, and so he had to work summers at an industrial laundry, you know, washing sheets for hotels and stuff like that. So that was kind of their starting point.

The but

books were everything to them. You know, they met in a poetry workshop. And when I was a kid, you know, it sounds very Victorian to say, but after dinner, we'd all gather together in the den, not to watch TV, but to pass a book. I remember very clearly. That's how I read The Lion, the wicker, the wardrobe, because we passed that book around as a family. My dad would read five pages. My mom would read four. My sister would read three. I'd read two, and my brother would read one. We'd read aloud. So I got used to, you know, when I do a reading in public or something, I have ideas about how to deliver that, because I've had a lot of practice reading aloud to others, going back to childhood. And, you know, my dad was always looking to maximize his writing time and his reading time. And in the 80s, the audio book market was barely existed. And what you could do is you could walk into a B Dalton and you could get, you could get audio books, but they were always highly abridged. It would be a whole Ed McBain novel squished down into two long playing cassettes. So really, you were getting, like, you know, it wasn't Ed McBain. You were getting half the book. If you were listening to, you know, a jack Higgins novel or something, you were getting maybe a quarter of the book. What a hideous I mean, thought makes me, you know, my skin crawl, just to think about it. My dad had some ways of getting unabridged books, but he also, there was, there were a few specialty companies that did the whole it was fairly expensive, but you could get the whole book on audio cassette. He got all of lonesome. Dove. By Larry McMurtry on something like 26 cassettes I actually have. It was read by a guy named Wolfram Kathe insky, who was terrific reader, reader. I've actually got those box sets of audio tapes in my basement right now. But the other thing is, is he hired his children to read books on audio for him. So my sister, myself and my brother all read Larry block and Donald Westlake and Harold Robbins and read this stuff on audio tape for almost 20 bucks. In audio tape was good walking around cash, you know. So it's very literary stories where the threaded through the right into the tapestry of the family from the beginning. Yeah.

Michael David Wilson 10:40

And I understand too, it wasn't just through reading that you experience stories and horror because, I mean, by age nine, you were in the wraparound segments for George A Romero's creep show, right?

Joe Hill 10:57

I mean, I sometimes talk about, you know, it seems obvious that I should given that my dad is steve King. It seems obvious that I wound up writing horror, but there were actually a few other influences there that played a really important role, and one is I was cast in creep show when I was eight years old. I played bill. I play Billy, the kid with the voodoo doll who gets even with his father at the end of the film. The movie was made on a low budget in Pittsburgh, and I want to say 1981 independent film and child labor laws have come a long way in the years since. So now, if you have a child actor, you know you have to have an on set tutor and an on set nanny, and I think they're a lot stricter about how many hours the kids can work, although I didn't work. I mean, they were quite reasonable with me. They didn't have anyone to look after me on set. There was no professional hand to watch out for the eight year old. So George Romero thought about it, and he stuck me in the trailer with Tom Savini the master of gross out special effects, and that's where I spent the week that I shot my part was in Tom savinis trailer, and I've often talked about how he was my first rock star, you know, Tom wore motorcycle boots and a leather jacket, and he had these arched eyebrows like Spock and Star Trek. And he was just his fucking cool, you know, he he, I'd sit there under the under the his workbench and watch him disfigure movie stars with latex appliances, or, you know, or work on one of his fiends, one of his monsters, a rotting corpse, or the thing that came out of the crate in the middle segment of the film. And, you know, I saw the behind the scenes stuff where they basically had a reverse vacuum to pump cockroaches out of, out of a, you know, latex corpse, a fake corpse. And I was just completely fascinated. I wasn't repelled or frightened or upset about about it. I remember he had a book of autopsy photos, and I was curious. And so he sat with me and looked at them and said I didn't have to look at anything I didn't want to look at, but if he was I was curious, he'd be happy to talk to me about it. And I was at that age before, you know, some things are supposed to be upsetting. So I wasn't upset. I just thought, oh, how natural, how normal. That's what someone looks like when they're dead. That's interesting. And he never talked to me like I was a kid. He just seemed to treat me like I was a grown up peer. And I just came away feeling like, man, that's what I want to do when I grow up. I want to kill people in really fascinating, memorable ways. And I want to invent, you know, memorable creatures, which is what I wound up doing. I just, I just do it on the page. And after, not long, after my experience on the set of creep show, I began, I was probably a couple years older, but I began reading Fangoria magazine. So Fango to the faithful. Fangoria was this long running magazine dedicated to horror movies and horror novels and the comic books and TV, and especially made big stars out of guys like Rob Boughton and Tom Savini and Stan Winston. And, you know, the masters of that era of practical gross out effects. And, you know, I read Fango cover to cover that was like my Time magazine. I had strong opinions about every horror film that came out because, you know, I knew all about it from reading Fango and and Fango people forget, but the original run of Fango, those magazines. Had centerfolds in them, sort of like Playboy and the other lad magazines have centerfolds. But the thing is, is in Playboy, the centerfold was like, you open it up and there's a, you know, hot girl wearing a pair of socks and a smile and nothing else, but you open up the centerfold of Fango, and it's some Gomer with an ax buried in his head and his eyeballs bulging out, and, you know, Gore spattering everywhere. And I pulled those, those centerfolds, out and taped them up on my the wall of my bedroom in a completely unrelated bit of trivia, I held on to my virginity for a really surprisingly long period of time. Who could fathom it

Michael David Wilson 15:43

completely coincidental? Related? I'm sure so.

Joe Hill 15:49

So, I mean, I always, you know, no pun intended. I had it in my blood. It was, it was always, you know, I loved horror films from an early age. I loved reading this stuff. It goes without saying. I was a huge Stephen King fan. Maybe we'll talk about it. I did. I did try my hand. I went through a little period of thinking like, how am I going to do this? How am I going to be a writer when my dad is steve King, that was in college, and that's when I dropped my last name to write is Joe Hill, so people would know about the connection. I was able to keep it secret for a fairly long period of time. But the other thing I did for at least a little while was I stopped writing horror and dark fantasy because I thought, you know, Steve king's son can't write this stuff. It just looked like he's grabbing his dad daddy's coattails, you know. And so I tried my hand at writing New Yorker stories, the kind of fiction that you found in like the Atlantic Monthly in New York, the New Yorker and stuff. And me, of course, the problem was that I didn't really like that stuff. I didn't read the New Yorker. I was a Fango guy, not a New Yorker guy. I didn't read Cheever and Updike, you know. I knew about Richard Matheson and Ray Bradbury, you know. And so it was a really unnatural fit for me and and the stories, the stories were boring. They got turned down everywhere, and I'm not surprised, they weren't interesting to me. So how could they possibly interest an editor? They did have some technical polish I, I, you know, by the time I was in my early 20s, I'd say, on a sentence by sentence level, I was a pretty polished, you know, stylist, but the stories themselves had no internal life. They were just dead on the page, you know. And I only really found my way when I gave myself permission to write horror fiction, to write fantasy and dark stuff, and I and the and and the pen name. Sorry to blab on, but, you know, to finish the story, the pen name is what gave me permission to write horror because I thought, well, Joseph King can't write horror fiction because he looks like he'd be look he looked like he was grabbing his dad's coattails. But no one knows who Joe Hill is. He's just Joe Schmo. He can write whatever he wants, you know. So it freed me up to write the kind of stuff that I actually like to read. And shortly afterwards, you know, after I made this decision, I wrote a story called Pop Art, and which is in 20th century, ghosts. And, you know, it's the first story. It sold in the third place I sent it. And as the first story I wrote that I was, you know, really, really proud of really excited about,

Michael David Wilson 18:22

yeah, I think pop art might be the first story that I read by you. I think it's the one that a lot of people were like, You got to check this out. You got to buy the collection. But you've got to read pop art.

Joe Hill 18:34

Yeah, I think I wrote that story. I think I wrote the first draft of that story when I was like, 2829 or something. It's been all downhill since then. I peaked early. You know. But for those who don't know, pop art is in my first collection, a book of stories called 20th century ghosts. It's my it's it's, there's only one story in that collection that's even older than pop art, and that one is about pop art. Is about the friendship between a juvenile delinquent and an inflatable boy named Arthur Roth. Arthur is made of plastic and filled with air. He weighs about six ounces, and if you ever sat in a sharpened pencil, it would kill him. And in the story, it's explained that this is just a genetic condition that skips generations sometimes, and, you know, and otherwise the story is played completely straight. And I had a lot of fun writing it. I'm, you know, and that one seems to have stuck around a little

Michael David Wilson 19:23

bit, yeah, and since release in the short story collection, then you wrote heart shaped box, and then after that, like the the novels have got meatier and meatier in terms of just the length for them. So, I mean, I'm wondering, what are the kind of challenges that you face when you know, graduating from short stories to shorter novels and then to these epic novels, and what do you think are the advantages

Joe Hill 19:54

even king size books? Well, Stephen King Ian scale novel, yeah. That's it. That's it. So I sort of stumbled backwards into writing the first novel, because, as I've said elsewhere, and, you know, it's kind of some, you know, it's old, old info. People have heard me talk before on interviews. Well, they will have heard this one once or twice. But, you know, basically I was a failed novelist. You know, by the time I was 30, I had written four books that no one wanted to buy. You know, I took my best swings with them. But, I mean, the last one was called the fear tree, and it was big. It was as big as Nosferatu. And you know, it's turned down by every publisher in New York, every publisher in London, and for final degrading kick in the crotch, it was turned down by every publisher in Canada, which is proof that no matter how low you fallen, there's you could still fall further, you know, further yet. But, you know, so by the time, so, so by the time I was in my, you know, very early 30s, I'd pretty much given up on the idea that I had a novel in me. I felt like, you know, I really wanted to do this, and I really thought I'd be able to pull it off, but I've taken my best swings, and it wasn't in me, you know, people those books were not things people wanted to buy. I guess I don't know how to do that. I I had figured out how to write a short story. I knew I could write a good short story. I had written short stories that were in Best of collections, and short stories that had been nominated for prizes or won prizes, and and I had enough short stories to make a collection, and I thought, Well, I I was never able to publish a novel, but maybe I can sell a book of short stories, and there'll be some kind of triumph in that, you know. And also I had, by then, I had sold an 11 page Spider Man story to Marvel, and I had started to think, fuck novels. I'll just be a comic book writer. I can do this. I get comics, you know, and people like my comic book scripts. So the book short stories 20th century ghosts that was also turned down by all the major publishers, but it wound up in front of a terrific horror and fantasy writer named Peter Crowther. Peter has a collection of his own called the longest single note. That's a wonderful compilation of his best stories and highly recommended, really, just terrific genre wanderer. You know, he writes fantasy, Light Fantasy, you know, horror, suspense, science fiction. I love Pete's stuff. But anyway, Pete had a small press of his own called PS publishing, and he read a few of my stories, and on the strength of pop art, almost completely on pop art, he really liked best new horror and the title story, 20th century ghost as well. On the strength of those three stories, he decided to do a limited run of my collection, and that's how I broke through. That's how I finally got a book that was in 2005 Pete asked me to write two more stories for that book. And so because he said, all these other stories have been previously published, let's offer reader something they can't get anywhere else. So I did two new stories, or I started two new stories. The first one was called the cape, and that one turned out pretty well, and is one of the best stories in the book. And then I started this other one called Dead Man suit. Dead Man suit is about a heavy metal musician named Judas coin. He's in his 60s. He's had a pretty successful career, you know, platinum albums, world tours, but now he's on the down slope, and he's banging around his upstate New York mansion all by himself. The only one up there is with him. Is his groupie, much younger groupie girlfriend, and they're on the outs. They hardly talk to each other. The only thing that really brings him pleasure is he's got a cabinet of curiosities. And in that cabinet of curiosities, he's got a witch's confession from the 18th century. It's got a tree pan, human skull, it's got a snuff film. And he, he hears about someone selling a haunted suit online, and he decides he's just got to have it for his collection. And like anyone listening to this podcast, you know, can tell just hearing that that this is a terrible fucking idea, but he, he buys the suit anyway, and it turns out the ghost attached to it is very real and very dangerous. Then I always thought that Jude, who was kind of a prick, I always thought, you know, Jude would realize his mistake too late, and the ghost would eat him for breakfast by page 30, and I'd have one more story for Pete Carter. But A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the ending, which is that Jude wouldn't die on my schedule. Every time I stomped on him, I'd lift my shoe and he'd scuttle away again like a cockroach. And it became kind of fascinating to see how long he could keep running. And it turned out he could keep running for 300 pages, and that's how I wrote my first novel, you know. And and along the way. I kind of got to like Jude, and I kind of started to think he's not as bad a person as we thought he was when we first met him, that a lot of that rage, a lot of his cold, aloof nature, was actually sort of a defense mechanism against a guy who had been hurt a lot of times, who had suffered a lot of damage and didn't want to suffer anymore, so, but that was a nice, lean mean. I mean, I see you got like a Dean Koontz there on the back here, on your bookshelf behind you, Michael, you know, it was like a Dean Koontz, like, you know, an early Dean Koontz thrillers, you know, ran hard as a road story. My hero spent a lot of time with this ghost after him, chasing him like the Terminator, you know, and and then, and then I wrote a follow up called horns, which was about the same size, a different kind of book. It's, it's kind of a horror novel, you know, it's kind of horror Jason. It's kind of like a horror comedy in a way, or horror tragedy, or horror, tragic comedy. I sound like Polonius and Hamlet the horror, tragic comedy. So, so then, then, you know, hardship box had done really well. Horns had done okay. It was published. It It took a few years to get written, and it was published after the big financial crash in 2008 and although it had a couple weeks on the bestseller list, I knew the publishers were a bit disappointed, but two things happened that made me think, Oh, I might be okay. One is, they began filming a TV series based on my comic book lock and key. And that gave me a little cachet. And then Daniel Radcliffe signed up to make a movie out of horns. And it's, you know, in some ways, Daniel Radcliffe did a lot to save my my career when it was in not such a great place, by agreeing to make that film, you know. And but I just thought, Okay, the next book, the next book has to be a home run. I really have to crush it, you know. And I decided to consciously, kind of try to write a book that was the sort of book that my dad is well known for, I decided I wanted to write a big multicast, you know, horror novel that took place over a fairly long period of time and had a lot of big set pieces, and I had an idea for a pretty distinctive and memorable monster at the center of it, a road vampire named Charlie Manx who feasts on the souls of children. And I thought I could run with it. And so, you know, so the next book was, the next book was longer by design, because I felt like I had to go bigger. I had to establish, you know, my commercial bonafides and and, you know, really want one to, you know, get readers excited and build my following and all the rest of it. And I had a story I loved. I felt like, you know, I had a character, Vic McQueen at the center of Nosferatu that I was excited for. And, you know, I just felt like I could really open up the throttle and run with that one. So that's how I wrote the that's how I wound up writing a long book.

Michael David Wilson 28:27

Yeah, and so with heart shaped box, I mean, you really just started with this initial premise, and then you ran with the idea. So presumably, in terms of, you know, initial planning, there wasn't so much planning, it was more we're writing, we're seeing where it's going. Is this something that you have kept up with to this day? Because if

Joe Hill 28:53

you ever outlined, yeah, I think outlines are garbage. I think they're really bad idea, you know, I mean, my, my, my approach is, I try to come up with a concept that feels exciting and fresh. You know, I, I had an idea for a story about a worldwide pathogen, a disease, kind of, you know, a virus, novel like the stand only, instead of killing people by Super flu, people would be incinerated by spontaneous combustion. I thought there's something there that's an exciting, that's an exciting idea, plague of spontaneous combustion that hasn't been done before, you know, and so, so you get the concept, but then what I want, I want to apologize to all the listeners for the squeaking they just heard. That was me getting comfortable in the easy chair. You know, it, it. It's great to have a high concept, a sticky high concept, but I need characters to care about. Are characters I can fall in love with. It takes months or years to write a novel. These are people I'm going to spend a lot of time with. They have to be interesting. I mean, I actually view each character almost as a kind of mystery that I'm going to pick apart. I want to know who they are, how they feel about the world, what excites them, what breaks their heart, what has broken their heart? You know, what are what are their defeats look like? What do they count as their personal victories? What are their regrets? What's broken them as a person? You know, this is all stuff. I'm going to use the book to find out and and every novel and every short story is simply a thought experiment where you take a particular, sharply defined individual and plop them into a situation and then see what happens and and if you do that, you don't need an outline and you don't need to plan, the character will always be so much more make much more interesting choices than you ever could have planned if you just let them be themselves. This is going to start to sound a little Woo, woo, new agey, you know, a little bit, I don't know, a little bit out to lunch, but you know, there is this thing about writing character. You have these authors who will say, you know, all my characters are based on me, they're all somehow autobiographical. And I think that's ridiculous. That's what a ridiculous way to write leaves no room for observation. Most of my characters are nothing like me and are not drawn from life. I'm not looking within. I'm looking outside at the people around me and trying to figure them out, you know? I don't know. I'm not a 60 year old heavy metal musician. I've never done a world tour, you know, and all I've done is read some issues of Rolling Stone magazine. I wanted to get inside Jude, but Jude is not me, and the reason he didn't die on my schedule in heart shaped box is he kept making choices that I never would have thought of and never would have made. And I know this is where it gets kind of new agey, because you're saying to yourself, Joe, you thought him up. Every choice he made is obviously a choice you could have made. You thought his choices up, but in some, in some weird basic way, I didn't, not really. I was just watching him. He only existed in my mind. But it's still more like an act of observation than imagination, where this character that seemed very clearly formed, you know, on a sort of moment by moment basis, was Free to make choices that he would obviously make, but that maybe never would have occurred to me if I hadn't been spending time with him. So I know that's weird sounding, because it kind of insists on a life, separate life to these characters that I did, in fact, dream up, but to me that separate life is real. You know, while I'm writing the story, those characters really are free to do what they want, and in some way, you know, are constantly surprising me.

Michael David Wilson 33:19

No, a lot of what you're saying here, it really resonates. And I've often found when I'm writing and when I have a kind of writing challenge or does what some people would term a block, although it's never a block for for too long, but I'll often find that the solution is already baked into the story, or that the character is already foreshadowed, what's going to happen anyway,

Joe Hill 33:46

always, always, it's already all there. Always, yeah, I think that. I think that a lot of times when you get stuck in a story midway through a story, it's because you're trying to force your characters to do something that they don't want to do, and that deep down, you know they wouldn't do, you know that they wouldn't, they wouldn't agree to split up in the old swamp or something. You know, they're just too smart. They wouldn't, you know, they couldn't be talked into that choice, whatever. And and what you're thinking, you're you're panicking, because if, if they don't take the next step, then they won't take the step after that, then they won't take the step after that, and then you won't get to write that scene you've been planning for two months, because you're never going to get to that scene, because they're going to turn left instead of going straight ahead. But you know, if you let them turn left, they always take you someplace more interesting anyway, you wind up writing an even better scene because, you know, because it's true, it feels authentic and honest.

Bob Pastorella 34:47

I was gonna say this makes me feel a lot better about the last time I tried to plot something. A couple months ago, I spent and wrote about 50 pages in a notebook of. A basic story that is going to be, you know, pretty, pretty involved. And when I felt like I was comfortable enough to start writing about it, what do I do? I go way before the fucking story starts right? My main characters are teenagers. And go, Okay, I'm starting here. And as I'm going through all these characters that I created that were going to cause problems as I'm writing this I'm like, the character I needed is right here the whole time. Yeah, you know it's like, what? Why do I need? Why do I need this guy when I have this person right here who's been here the whole time, and so do I feel bad about spending all this time about writing an outline and, like, because I'm notoriously a pants or I did not plot anything, and I'm like, you know, I'm gonna, I'm gonna try this again for the umpteenth time. And do I do I feel bad about that? No, because I have some ideas. I have some some some set pieces that I know I want to do that I want to get through. Yeah, so I feel like that writing an outline should be about the events and have very little to do with the characters. Because the reason why I started those characters so young is because I wanted to find out about them who they were. You.

Joe Hill 36:22

Yeah, I don't really, I don't really think that there's wasted work. There's some poet who said there's no such thing as the wrong step. There's just the next step. And I look back now on the books that I was never able to publish, and boy, I pulled all kinds of things out of those books over the years. It's in in my most recent novel, King sorrow, probably, which is probably the last long one for a while, but in the most recent one, the first part of the book is called The Briars part one, but the Briars is also the title of my last unpublished novel, and I used the location in that unpublished novel as Colin wrens. One of the characters is named Colin Wren and he lives there with his grandfather. And I just took the whole setting from the briars, which I had always seen very clearly, and plopped it down into King sorrow. There was another failed novel called the surrealist glass that I started work on between heart shaped, you know, heart shaped box and horns, and then I quit it because it sucked donkey dick. You know, it was just, just absolutely dreadful novel, but, but it did have this interesting supernatural object. Had one good character, and it had an interesting supernatural object, the surrealist glass itself, and and I, I took that glass and I lent, lent it to one of the characters in King sorrow, and it was like it finally found its place. That was where it was always, you know, I wrote part of the surrealist glass so I could, metaphorically have the glass in my back pocket and pull it back out later when I needed it for King sorrow. So everything you've ever written was an early draft of something you'll write later that might actually be good. All the bad stories were early drafts of good stuff that was, you know, going to come later, right?

Michael David Wilson 38:32

Yeah, I see it as a kind of training. And it's not as if, when we go to the gym and we're lifting that if we fail or something, we're like, oh, well, that was a complete waste of time. You building up for the next part, and I see that as analogous and as accurate with writing as well, well.

Joe Hill 38:55

And also, I mean, let's stay with that metaphor for a second. You know, one of the things the weightlifters talk about is lifting to failure. You know that you can really build the muscles if sometimes you lift a failure, and I think that's true for early short stories or early novels everyone wants. You know, if you spent two years of your life you got a full time job and a marriage and a kid, you don't have the time to work you want, but it's your hobby. And over two years, you write a novel, and it's your first novel. No one wants to hear it sucks. You put your heart into it. It was really important to you. You love the characters, you know. You had good concepts and stuff. No one wants to hand it over to their friends or their wife or an agent. And here, it's not very good, you know, and, and, but those early failures are important. Don't give up. You did good work, you know, even if, the even if that book, that first book, is not publishable, you know, you wrote it for you, and you lift it to failure. You built muscle. You know, the next time. Time, you'll lift more, you'll be more capable, and more of the story will come together, you know, I mean, for sure, if you're a non professional, you know, if you love doing it, don't stop, because you haven't succeeded yet, you know. And also maybe change your idea about what success looks like. I I think there's also that I changed my idea about what success looked like after a certain point. You know, I, after a few years of flailing away and not being able to sell any books, I started to think, well, if I sold a book of short stories, that might look like success. If I, I would say to myself, if I can get in this anthology, that would be success. There was an anthology called there was a there was a call out for submissions to an anthology called the many faces of Van Helsing. It was going to be a book of short stories that would come out the same time as the Hugh Jackman Van Helsing film. Gene cavallos was the editor. So it was sort of like it wasn't an official tie in, but the idea was to kind of draft off all the publicity for the Van Helsing picture. I heard about this open call, and by then, I had written a few short stories that had done okay, won some prizes and stuff and but I hadn't. I didn't have a readership. I had never been published in any really big like journal or book or anything. And I saw about this, and I saw it had a big publish was like Signet or something. And I thought, I'm getting in that fucking book. You know, that's what success looks like, if I can get in that book. So I wrote a story called Abraham's boys. I thought it through. I thought, what can I write about Abraham Van Helsing that hasn't been written? And I had a few ideas, and I had an approach. I wrote a short story. I think it's one of the better ones in 20th century. Goes I got in the collection. I was one of only three or four people, you know, who are total unknowns, who got in that book, you know. And hey, I mean, you know, you get, you get a story published in a small journal, or something like that, you know, small horror journal with some some other writers you admire, that's success, you know. So, yeah, I'm big fan of, you know, amateurs. Keeping going not you know, don't quit on yourself if it's fun, and don't make your fun be about you know, your your exterior triumphs. You know, keep the focus on, what do you enjoy writing? Did you finish the book? Did you get your pages? Did you write a good scene, scene you're proud of, you know, and just keep lifting till failure?

Michael David Wilson 42:30

Yeah, I think there's a lot of self imposed pressure these days, and it's perhaps because of this kind of social media always connected age that we're living in, but where people, rather than just looking at writing the story, they're looking at these other metrics, like they're looking at the Goodreads reviews, they're looking at getting on the bestseller list. But really, Josh Malerman, the author of bird box and incidents around the house, he says that the only success, the only making it, is making the art itself. It is finishing that story. And that's something that's always stuck with me. If you can find joy in the pursuit of writing itself, then whatever happens, you win every time. Mean.

Joe Hill 43:22

Mean, this is why. This is why. You know no one who loves, who wants to be a writer. And you know, if you admire, if there are writers you admire and you want to write your own stuff because you love their work, you know you don't want to go anywhere near AI. You don't want to have anything to do with it. You know, don't touch it with a 10 foot pole or whatever, because, you know, the musician who writes a song using AI didn't really write anything. That's like a child turning the crank on a music box and imagining somehow they created the song inside the music box, but you didn't create anything. All you did was turn the handle on a device and it produced a sound, you know, and and, and as far as writing can be tremendously frustrating at times and slow and hard work. Don't let anyone take that work away from you, though. That's that's where all the meaning is. That's where all the joy is, you know. And I heard an interesting thing a little while ago from an editor, because they see a lot of AI manuscripts now in the slush pile. This editor said, You can always tell when a manuscript was aI created, because when you talk to the writer, if you read three chapters and then you talk to the writer about it, they don't really know their own book the way a writer who actually wrote every sentence made choices about the characters, made choices about the plot, knows their. Own story, you know, and cares about it and has an intensity to it, you know, an intensity of connection to the material that they wrote. And the person who just turned something out through AI doesn't have that intimate, you know, link with it, and it shows pretty quickly when they start to talk about the work. So, so. But I just, I just can't imagine, you know, it would feel so hollow to turn something over to readers where you didn't really craft it, you didn't really come up with the plot, come up with a character, struggle with every sentence. I'm blanking on the writer of science fiction. There was a science fiction writer who was writing about AI in the Atlantic,

author of the

short story that led to the movie arrival. He said, You know, every work of fiction is the result of 1000s of creative choices made day after day. You know, page by page, sentence by sentence, 1000s upon 1000s of creative choices and and you've skipped all those choices the moment you process something via AI, the moment you turn to AI for creation and and so the end result is there's no artist involved with the art which makes the art itself fundamentally meaningless. You know, it's there's no person there. There's nothing there. So, yeah, yeah, it's like, it's like reading something that was written by an AI novel would be like making out with an inflatable sex toy,

Michael David Wilson 46:54

which, whilst it worked for Ryan Gosling in

Joe Hill 47:01

want to have? I don't think, I don't think that that's really a healthy, mature relationship is you know, you want to have relationships with people, yeah, even if they're people you'll never meet. But you've met their you've seen their mind at work on the page

Michael David Wilson 47:20

and the short story writer you reference that is Ted Chiang, just for right, Paul, right.

Bob Pastorella 47:28

The way that I explained it to a tech bro about AI was, what if someone created a mod to help you, not just help you, but just beat the bosses in Elden ring. Oh, no, no, no, no, that's not same thing. Yeah.

Joe Hill 47:45

It is, yeah, it is, yeah, it is, that's but,

Bob Pastorella 47:49

but then, but then you wouldn't have a sense of accomplishment. I think I get it now, yeah, it's imagine and go away.

Joe Hill 47:58

Now, Bob, imagine you open up the New York Times crossword in the morning, and then you scan it with your phone, and the AI fills in all the answers. And then you write, you copy the answers off your phone onto the why, I can't imagine. I mean, just, just, just go wank off. It'd be more fun. It'll come to the same thing. And I mean, like, why, you know, and that's, and that's kind of how I feel about, you know, the idea of of AI writing and AI film clips, and I find AI music especially obscene, makes me, makes me fucking ill. But anyway, let's we don't need to. You don't need to hear my whole rant. Just, I, you know, I just, it's like music. I have this view that like music is at the center of everything, and that music is the most beautiful art form, and that I heard one of these AI engines is producing 9 million songs a day now, or something. It's just, I don't know, some scenes like someone taking a piss on your mother or something. It just feels so it just feels so fucking wrong. I hate the idea, you know anyway,

Michael David Wilson 49:23

yeah, well, I think we are all in agreement on AI in this conversation, and I'm sure the vast majority of our listeners too. But you know, talking about music, what was the music that you were listening to while writing King sorrow.

Joe Hill 49:42

So so every story I've ever written has had a collection of tunes behind it and and you know, most of the books have had playlists that I turned to to get in the right mindset. But I worked on King sorrow for a long. Time, I spent three years writing King sorrow, maybe even a little bit more. And so it's impossible to really condense three years of musical wandering into one record or two records or something. I mean, you know, I went through phases. I I was listening to a lot of Oasis, but I always listen to a lot of Oasis. Listen to a lot of Liam Gallagher, but I always listen to a lot of Liam Gallagher, Mumford and Sons, The Lumineers. You know, there's a lot of this kind of Chris Stapleton, you know, great. He's country rock, but, but in the 70s, he would have just been rock and roll. He would have just just been a guy like Bob Seeger. So Bob's nod and Bob's like, you're a Chris Stapleton guy.

Bob Pastorella 50:52

I'm all kinds of music guy. But yes, I listen to, I listen to everything, man. I go from, you know, from Coltrane to Slayer. So I've got my

Joe Hill 51:02

covering stuff where you're like, How did I miss this? I mean, just in the last couple years, I've discovered how great Nazareth was back in the day. I just, I think I stayed away from when I was growing up, because I thought they'd be too hard for me. You know, that hair of the dog and stuff like that would just be too you know, we just go too hard. I loved Zeppelin and AC DC. But I think I thought that, you know, that that Nazareth was going to be like Megadeth or something, that it was going to be speed metal or and then I've, then a few years ago, I started listening to, I thought, this is exactly the kind of thing I love. I love this kind of, you know, this is, this is right, my sweet spot. Why did I wait so long? I am, look, I'm a 50 something American, dad. I walk into the supermarket. Any money is playing. I'm like, Wow, this place rocks. Let's buy some eggplants. This place rules. Unless Stevie Nicks comes on, yeah.

Let's go get some milk. So yeah,

Michael David Wilson 52:05

there you go. I mean, who can't like Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac? What would be wrong with you if you didn't, quite frankly,

Joe Hill 52:13

Lindsay Buckingham, I think he's got a new solo album coming out. You know that Buckingham Knicks album that was sort of like a lost classic from 73 has just re emerged digitally. That's a great record that's got some terrific stuff on it. There's two or three tracks on it that's as good as anything on rumors. There's two there's two tracks on it that are rumors level. So yeah, the it's easier sometimes with short stories, because short stories, because short stories don't stick around long enough to get more than four or five songs attached to them. Yeah, but books, a book that takes two or three years. I remember with Nosferatu, I listened to a lot of Steve Miller, and

some of that comes through in the book, you know,

I think that Vic thinks about, you know, abracadabra, I want to reach out and grab you when she's a kid and she first discovers her psychic powers.

Bob Pastorella 53:08

Do you read while writing? Or is writing a solitary thing, and you can't, you can't read anybody's work while you're writing.

Joe Hill 53:18

I know some read. I know some writers who say I never read fiction while I'm working on a novel? Well, if I never read fiction, I love fiction. I love to read. I love novels. I love other I love other writers. I'm a lot more interested in other writers than I am in my own writing, you know. And if I never read novels while I was writing my own novels, I guess I would never read novels, because I'm always writing a novel, you know, so I did for a few years. I was a huge horror fan right up through the 90s, the early 90s, and then around the mid 90s, when I started trying to get published, and maybe more in the more towards the late 90s, I guess I started reading less horror fiction because I didn't want to be influenced by what other people were doing. But I got over that, like, about six or seven years ago, and now I'm back to reading horror fiction is mine. I don't really why. I think that's a, it's a, it's an understandable concern, but that's a young writer's concern, and and, you know, isn't, I don't think is very valid. I mean, it's like, you know, I I'm not saying I can't fall under the influence of another writer, but I just, I feel like I have a sense for my own voice. And actually, I'm so used to writing stories the way I write them, and my voice is so sort of, you know, it's just the way I write, it's just the way I think about sentences and paragraphs and stuff that, actually, I don't know what I could read that would kind of pull me off that, you know, be really interesting, if something could sort of pull me out of that. But. You know, that ditch that I've done for myself, that you know, my general approach, but I don't really feel like, you know, I can read someone like Keith Rosson coffin moon and just be blown away. Just be like, What a great book, you know. But I'm still stuck writing books the way I write them. I can't figure out how to write them like Keith writes them, you know, I can't. That doesn't mean I can't learn. I'm not trying to, you know, I was thinking I about 10 years ago, I fell in love with a TV show called Foyle's war, a fair play mystery series out of England about a detective, a kind of Sherlock Holmes, her girl perot type named Foyle. Detective superintendent. Foyle who lives in a small town on the coast of England and solves crimes during World War Two. He's too old to fight. He wants to fight, but he's told to remain a cop. And I loved those mysteries, almost all of which were written by the great crime writer, Anthony Horowitz. And then I moved on into reading Anthony Horowitz's novels, which are also fair play mysteries. And a fair play mystery means all the clues are there on the page, and if you're really clever, you can solve the mystery alongside the detective, or maybe even beat the detective to the solution. The fact is, if it's ingeniously constructed, you're never going to beat the detective to it. That's just not going to happen. You're not smart enough. You know, I'm not smart enough. You're not smart enough. It's not happening. Although I watched so much oils war that towards the end, sometimes I did spot it. I started to get to I started to think, oh, wait a minute, that was just a bit of misdirection. I know what we were supposed to really pay attention to in that scene. And it wasn't this. It was that other thing. So anyway, I've read a lot of Anthony horror wits. I've watched all his TV shows and stuff, and gradually, I kind of absorbed how to do a fair play mystery, and I've written a few. Often I try things out in comics before I try them out on the page. So I wrote a fair play mystery called shit talk homes. Probably my I think I mostly, most of my stuff has landed pretty well. Shit talk is the only thing I ever wrote where I think mostly people didn't that one, you know that one kind of belly flopped. I like it, but it's not really, I don't think it's really what my readers want me to do, but I still had practice with the Fair Play mystery. I was asked to write a Sherlock Holmes story by the Arthur Conan Doyle estate, and I wrote that, and I think that's a pretty good story, and that's a fair play one that'll be out like, some point next year, I think,

Michael David Wilson 57:43

and this shit talk Home Story is this available anywhere?

Joe Hill 57:47

Yeah, it's called

Dying is easy, which comes from an old, an old phrase I forget, who said it some some comedian of the 70s or 80s said comedy is hard, dying is easy, by which he meant dying on stage. So dying is easy is about a former city detective. We don't know what city. Maybe it's New York. Maybe it's Chicago. Could be Detroit, hard to say, but there's, there's this former homicide detective named Sid Holmes, who's got a mouth on him. He's very hard to like, and so around on the force. He was known as shit talk homes, and he's thrown he's drummed out of the force after a tragedy, and so he's sifting around for what to do with himself, and decides to see if he can make a go as a stand up comedian. So he's, his day job is as well. It's, I guess it's a night job. He's, he's working hard to try to make it as a stand up comic, and it's not clear if he's really funny enough, his humor is all very morbid cop humor. But there's another comedian who's on his way up, and they're doing the same club together, and this other comedian steals jokes. He's even stolen some of Sid's jokes, which is a huge crime in the stand up community, stealing jokes is an absolute no no. But this guy, this guy is on his way up, he's gonna be doing late night, you know, and he doesn't care, and he winds up dead. And everyone thinks shit talk did it. So shit talk has to find the real killer. And there's red herrings and misdirection and a whole set of suspects, and at the end, I think the solution does make sense. So it's done as a graphic novel through IDW, and has terrific artist named Martin Simmons, who worked on it, then later went on to do a big hit comic called the Department of truth. And Martin is great. It was fun. It was fun. But I think, I think my other. Comics lock and key basket full ahead plunge. That stuff is in the weird fantasy horror genre and and my readership likes that kind of thing, and I don't think is necessarily opposed to something that swings in the direction of crime, but maybe Sid talk swung too far that way. You know that it's kind of like, it's like, I don't know Columbo or something. I'm not sure anyone wanted me to write Columbo. I still was glad I did it. You got to do stuff that's you got to take chances and get outside your comfort zone now and then.

Michael David Wilson 1:00:38

You know, we are already coming up to the time that we have together, we've barely spoken about King sorrow. But, you know, people can just go out and buy the book, read the book. You don't need

Joe Hill 1:00:53

to really, really, the book speaks for itself. You know, the only way to you it really, it's less. We could talk about it for and we could talk and we could talk and start talking about King sorrow and talk about it for another hour. But, I mean, I think it's, you know, it's obvious that people just you want to enrich your life and grow as a person. The best way to do that is just experience King sorrow yourself by picking up a copy and hardcover ebook or audio available from all vendors at very, very reasonable prices, you know. I mean, it's rare to get so much excitement, so much fantasy and imagination, but also so much cultured wisdom between the covers of a single volume, you know, for one very affordable price. So, yeah, beyond that, I don't know that there's even anything else to be said about

Michael David Wilson 1:01:45

King sorrow. I mean, it's such a eloquent and polite pitch. I was just gonna say, if you like horror, read it. If you like fantasy, read it, and it's got a big fucking dragon on the cover. That was the pitch for me.

Joe Hill 1:01:59

Yeah, well, I was trying to be modest about it. I didn't want to oversell

Michael David Wilson 1:02:04

it. There you go.

Bob Pastorella 1:02:05

It's made me want to read more fantasy, which I'm, like, severely lacking in. In fantasy I grew up when I when Harry Potter came out, I was already at the age where I'm gonna go out and party and chase girls and all, yeah, and, you know, so I missed all that. I missed goosebumps. I missed all of that. Yeah, me too.

Joe Hill 1:02:26

Actually, I did read Harry Potter as it came out, because I had a professional interest, and then I kind of want to fall into the stories.

Bob Pastorella 1:02:33

And, yeah, I've never read any of

Joe Hill 1:02:35

and the writer turned out to be a little bit of a bummer, but that's a whole, another conversation. We don't got to get into that. The I yeah, I mean, we didn't touch on this. But, you know, of course, this is the, this is the this is horror podcast. And, you know, and, and the big elephant in the room is that some people don't think King sorrow is horror at all. I think it is. I think, I think that you know, especially in that it's one story about six friends who bring a dragon into our world. They smash reality and bring a dragon into their into our world, and then have to live with him for the next quarter century, and they have to find a new sacrifice for him every year for the rest of their lives, or he'll take one of them, and we get within one book, we get these sort of smaller mini novels where each of the characters becomes the main character for a while in their own tale, their own tightly compressed tale of suspense and the unnatural. And I think for sure that some of those stories are pretty outright horror. I mean, the second part two is called flight, flight of fright, and takes place on an airplane at 30,000 feet above the Atlantic Ocean, you know, on a flight from New York to London, and there's a terrorist on board, and there's a dragon outside the windows fighting F 16 and like, I mean, I think that's pretty scary, you know, and but Goodreads put it in the fantasy category when it was it got nominated for Goodreads, you know, fantasy of the year, instead of in the horror category. So opinions differ. I just want to say, I know we have to wrap things up, but I do. I just want to say that if King sorrow had been a werewolf or a zombie or a vampire, it would have been horror, because he's a dragon. I think some people feel that instantly makes it fantasy, but you have to ask yourself, why? Because they're all of these monsters are creatures of the imagination. They're all invented. Why is a werewolf definitionally horror, but a dragon is definitionally, you know, fantasy that doesn't follow with me. And also giant monster movies, you know, like them about giant and. Or the one about the giant spiders, those are horror films. Is Godzilla, fantasy, science fiction. I thought Godzilla was horror. But what's the difference between Godzilla and the dragon? I don't think there is one. I mean, in the later toe ho films, he can fly, for God's sake, kind of doesn't he fly in some of the later ones, you know, and so I think, briefly, that those kinds of terms, fantasy, horror, science fiction, they're very useful for booksellers. They're very useful for marketers. They don't always tell the reader all that much.

Bob Pastorella 1:05:36

No, didn't, didn't they call like when Peter Strauss floating dragon came out, didn't they call that dark fantasy? I'm pretty sure maybe very few people didn't call it horror. Yeah, maybe, I don't know. Maybe it's the dragon connection. You know, you got a physical dragon in yours. He had a metaphorical dragon.

Joe Hill 1:05:54

Is right? Yeah, I don't know. I don't know. Would it?

Michael David Wilson 1:05:59

This is what I was gonna say. I think there's bias from some people that immediately you mentioned a dragon. Now it's fantasy, but if you look at King sorrow, I mean, for goodness sake, there is a seance to summon the dragon, and then you have to sacrifice someone every Easter. It doesn't get any more horror than there's a monster.

Joe Hill 1:06:23

There's a monstrous and dangerous poltergeist in the book named Elwood Hondo, yeah, which is pretty hard. There's at one point, at one point, we're talking about giant spiders. At 1.2 of my heroes are attacked and attacked by a painting that comes to life. And it's a painting of 1000 little spiders, and the spiders are all biting them and crawling all over them, which is pretty horror. However, in that same section of the book, they're being led through a cavern by a troll. Now, that's pretty fantasy. So, you know, little bit of but what's wrong with mixing the chocolate and the peanut butter together? I thought that was a good thing. That's that mix of the sweet and savory that really makes a hamburger. You know, you want the you want the hamburger, but you want the sweet barbecue sauce on top. It's, you know, it's what gives it that zing. Hey guys, this was great. Thanks so much for talking to me. I had a blast.

Michael David Wilson 1:07:13

Yeah, yeah. Thank you so much. Do you have any final thoughts to leave our listeners and viewers with

Joe Hill 1:07:24

final thoughts.

Well, I don't know if I have final thoughts. I'll give you my final recommendations. They were in my newsletter too. My four favorite scary books of the year were cough and Moon by Keith Rosson, between two fires by Christopher buehlman, when the wolf comes home, by NAT Cassidy, and the devils by Joe Abercrombie. And then the four favorite films were sinners, dangerous animals, damn I'm gonna blank on one of them. The long walk was one which I actually think is funny place to in the podcast. But I actually think the long walk is one of the five best Stephen King adaptations. I really I like the hell out of that movie. What was the last one? What was the I don't know. I have a newsletter on sub stack. I think if you sign up, you can find the archive and look at the back issues. It's called escape hatch. And, you know, if you look it up on sub stack or go to my website, you can sign up for it, you know. And, and then I'm blabbing at you every month. Who doesn't want that. Listen, listen. Actually, anyone who's listening to this podcast obviously already has questionable taste, so they probably love my newsletter, you know, so you know, zip right on over to Joe hillfiction.com and sign up. Bob Michael, thank you

Michael David Wilson 1:08:48

all right. Thank you so much. Thank you so much for listening to Joe Hill on this is horror. Join us again next time when we will be talking to Eric larocker about his latest book, burnt Sparrow. It is a very thought provoking book, and in many ways, may be both his most experimental and most challenging book in all meanings of the word. Now if you want to get that episode and every other episode ahead of the crowd, plus the ability to submit questions to all the wonderful writers we chat with, including our next guest, Dean Koontz, then Become a patron@patreon.com forward slash, this is horror. Not only will you get a multitude of benefits, but in supporting the podcast, you are enabling me to live my dream and do this full time, something I am taking very seriously. Now you may have noticed the podcast has now. Releasing episodes twice per week, and we've really increased our video presence on Tiktok, Instagram and YouTube. So by all means, check out each of those, and if you like what you see, give us a follow the handle for all of them is at this as horror podcast. Okay, before I wrap up a quick advert break,

RJ Bayley 1:10:26

it was as if the video had unzipped my skin, slunk inside my tapered flesh and become one with me.

Bob Pastorella 1:10:34

From the creator of this is horror, comes a new nightmare for the digital age. The girl in the video, by Michael David Wilson, after a teacher receives a weirdly arousing video, his life descends into paranoia and obsession. More videos follow, each containing information no stranger could possibly know, but who's sending them and what do they want? The answers may destroy everything and everyone he loves. The girl in the video is the ring meets fatal attraction for the iPhone generation, available now in paperback, ebook and audio from the host of this is horror podcast, comes a dark thriller of obsession, paranoia and voyeurism. After relocating to a small coastal town, Brian discovers a hole that gazes into his neighbor's bedroom every night she dances and he peeps same song, same time, same wild and mesmerizing dance. But soon Brian suspects he's not the only one watching and she's not the only one being watched. Their watching is The Wicker Man meets body double with a splash of Suspiria. Their watching by Michael David Wilson and Bob Pastorella is available from this is horror.co.uk,

Amazon and wherever good books are sold.

Michael David Wilson 1:11:44

Now I said that next week, we are chatting with Eric larocker. One of the reasons is that we have invited each 2024 this is horror award winner onto the show and Eric's fantastic short story collection. This skin was once mine won the short story collection of the year. If you want to see the full list of winners, just head over to this is horror.co.uk, right now. Well, that about does it for another episode of This is horror. I'll see you next time for the fantastic conversation with Eric larocker. But until then, take care of yourselves. Be good to one another. Read horror, keep on writing and have a Great, great day.